566 Years After The Fall – Rome Lives…

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, September 13th 533, the Roman General Flavius Belisarius changed the history of the world by winning an unwinnable battle against the barbarian Vandals in what had once been Roman Africa, at a place known to us as AD DECIMUM, the tenth mile marker…

Humble milestones like the one pictured below marked each mile throughout the Roman highway system, spanning the 250,000 miles of roadway that once stretched from modern Scotland to Yemen. So extraordinarily durable was their construction that a number of those roads (and the bridges they crossed) are still in use today across former Roman territories in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Roman mile markers allowed the traveler to know precisely where they stood in relation to their departure point and destination, long before our slavish devotion to smart phones and GPS.

In what had been Roman Africa, stolen by the Vandals 100 years before, there stood such a stone on the approach to Carthage from the east on the ancient Roman highway that ran along the coast. To put this battle into a modern geographical context, note that where Carthage once stood in the ancientworld the sprawling metropolis of Tunis, capital of Tunisia, sits today (see map below). The actual battle took place at the tenth milestone from Carthage, known simply as Decimum Miliare (the tenth mile). This milestone, along with the battlefield itself has not been rediscovered by archaeologists as it lies beneath the suburbs of modern Tunis.

At that now lost tenth milestone (Ad Decimum), on this day – September 13th of 533 – the Roman Army led by General Flavius Belisarius (pictured below) met the Vandal King Gelimer in a battle that would change the course of history.

The world fully expected the Romans to fail as Roman armies had failed in the field against the Vandals and their Germanic ‘barbarian’ cousins for generations. Let’s recall which Romans sailed into battle against the Vandals – these were the Eastern Romans who had managed to avoid the fate that befell the Western Roman Empire for many reasons, not least of which was their geographical distance from the Vandals, Goths, Visigoths and other Northern Barbarians that had extinguished the Western Roman Empire in 476 with the formal abdication of the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus. The Vandal theft of Africa and their brutal sack of the City of Rome were undoubtedly two of the key events that made the loss of the West inevitable.

Now these Eastern Romans sailed straight towards mortal danger over 1,000 miles from home – having set sail with an invasion armada for the first time in decades (on ships that were specially built for the purpose since Rome no longer possessed a deep water navy). If they lost to the Vandals there would be no retreat and no hope of reinforcements. If Belisarius lost the battle at the tenth milestone, the Eastern Roman Empire would be in grave jeopardy. See below for something of Belisarius’ battle plan at Ad Decimum.

Belisarius and his Roman knights (see an image below for the decidedly medieval looking Roman knight that was very much the product of Belisarius’ experimentation with military technology and tactics) would triumph at Decimum Miliare against all odds and went on to extinguish the upstart Vandal kingdom and to bring Africa back into the Roman fold.

This was the first in a string of stunning victories engineered by Belisarius that would restore much of the lost Western Empire in the name of the reigning Caesar, the Emperor Justinian. These recuperated lands (Africa, Italy, parts of Gaul and Hispania) would remain part of the Roman Empire until after Justinian’s death – the moment when the ancient world truly ended and the Dark Ages began.

This moment, the battle that became known as Ad Decimum, figures prominently in the second book of my Legend of Africanus series: Avenging Africanus (available at amazon.com).

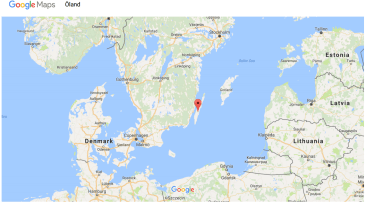

On a windswept island twenty times the size of Manhattan off the coast of Sweden, investigators are scouring a crime scene for clues, to understand who was behind a terrifying massacre whose details are only now coming to light. Yellow crime scene tape circles the remains of homes, and the remains of their former inhabitants, under a slate grey sky. Many dozens of people,  men, women and children fell victim to a horrendous attack on the island. Most remarkable is that the dastardly attackers had to overcome towering fifteen foot stone walls capped with battlements and manned by some of the most fearsome warriors Europe has ever known to commit their crime.

men, women and children fell victim to a horrendous attack on the island. Most remarkable is that the dastardly attackers had to overcome towering fifteen foot stone walls capped with battlements and manned by some of the most fearsome warriors Europe has ever known to commit their crime.

So what does it have to do with Rome?

To begin with, this attack happened some 1,500 years ago.

And the investigators that even now study this dark deed are archaeologists from Kalmar County Museum, located on the mainland just across from the island.

As described in Archaeology Magazine (link to the full article below):

“Built around A.D. 400, it encircled an area the size of a football field. Now called Sandby Borg, the site is one of more than a dozen similar “borgs,” or forts, on Öland, all built during the Migration Period, a tumultuous era in Europe that began in the fourth century A.D. and hastened the collapse of the Roman Empire.”

But there is more “Rome” in this story than simply the time period in which Sandby Borg was devastated by unknown assailants. Again quoting from Archaeology Magazine:

“Archaeological excavations and chance finds [on Öland] have turned up hundreds of Roman coins, bronze statues, glass beads, and vessels dating to

the first four centuries A.D., when Öland had extensive contact with the Roman Empire. As the empire began to decline, Scandinavian warriors from the islands of Bornholm, Gotland, and Öland found that a set of skills different from what they had sharpened before was now in demand. They had traveled thousands of miles south between a.d. 350 and 500 to work as mercenary bodyguards for the last of the Roman emperors, who paid well to guarantee their loyalty. Ölanders had long brought their wages back to the windswept Baltic island in the form of Roman solidi, gold coins commonly issued in the late empire. The solidi found on the island are distinctive, matching dies that have been uncovered in Rome. “A lot of them are very fresh, in mint condition,” Victor says, without the characteristic wear of coins that have been passed from hand to hand in trade. “There’s a direct link to Rome, and later to Milan and Arles.”

So this long, exposed island was populated by retired bodyguards that had enriched themselves in service of Caesar, the last Caesars to rule the Western Empire. And when they were released from duty they returned home with the gold that they had accumulated and they stashed that wealth in homes with turf walls that they raised behind massive stone fortifications knowing that word would spread of their wealth. That their hard won wages would prove to great a temptation in their horrendously violent age.

And that concern would prove to be terribly prescient.

Caesar’s bodyguards, and their families, fell not long after those protective walls were built.

Their story is dark, and fascinating, and well recounted in Archaeology Magazine for those interested in more..